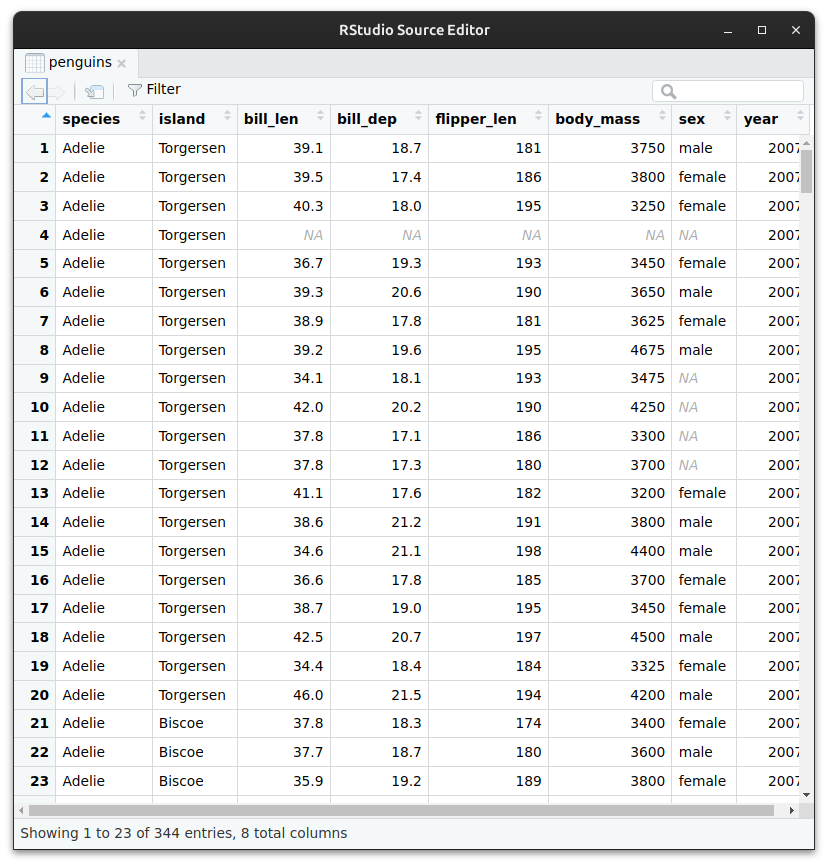

Rows: 344

Columns: 8

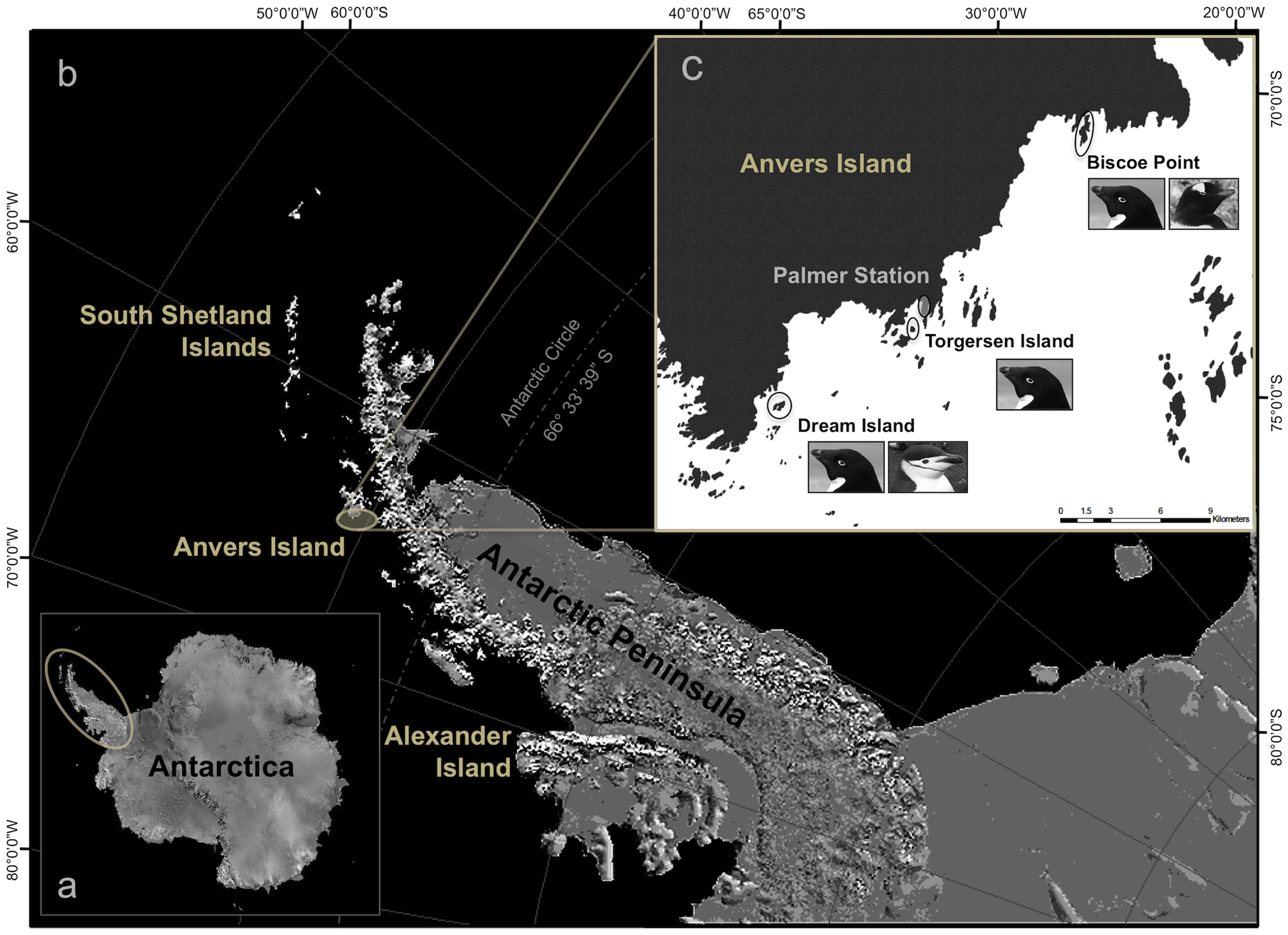

$ species <fct> Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adel…

$ island <fct> Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgerse…

$ bill_length_mm <dbl> 39.1, 39.5, 40.3, NA, 36.7, 39.3, 38.9, 39.2, 34.1, …

$ bill_depth_mm <dbl> 18.7, 17.4, 18.0, NA, 19.3, 20.6, 17.8, 19.6, 18.1, …

$ flipper_length_mm <int> 181, 186, 195, NA, 193, 190, 181, 195, 193, 190, 186…

$ body_mass_g <int> 3750, 3800, 3250, NA, 3450, 3650, 3625, 4675, 3475, …

$ sex <fct> male, female, female, NA, female, male, female, male…

$ year <int> 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007…

You can also click the object’s name in the Environment window.

You can also click the object’s name in the Environment window.