# A tibble: 344 × 8

species island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm flipper_length_mm body_mass_g

<fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7 181 3750

2 Adelie Torgersen 39.5 17.4 186 3800

3 Adelie Torgersen 40.3 18 195 3250

4 Adelie Torgersen NA NA NA NA

5 Adelie Torgersen 36.7 19.3 193 3450

6 Adelie Torgersen 39.3 20.6 190 3650

7 Adelie Torgersen 38.9 17.8 181 3625

8 Adelie Torgersen 39.2 19.6 195 4675

9 Adelie Torgersen 34.1 18.1 193 3475

10 Adelie Torgersen 42 20.2 190 4250

# ℹ 334 more rows

# ℹ 2 more variables: sex <fct>, year <int>Data wrangling

Data wrangling

What is data wrangling?

When we collect biological data, it never arrives perfectly polished. Files might have missing values, inconsistent names, or more information than we really need.

Before we can analyse or visualise, we first have to wrangle our data into a form that both we, and R, can understand. Part of this also involves checking if there are any problems with the data (like missing values), or anything unexpected that might be confusing (like columns with unintuitive names).

The word wrangle can mean either “to have an argument that continues for a long time” (chiefly UK), or “to take care of, control, or move large animals, often with difficulty or coercion” (chiefly North American). In dealing with biological data, either definition can sometimes feel appropriate!

“King Penguin Colony” (Aptenodytes patagonicus) by Scott Henderson, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Remember tibbles?

In the first session, we made some tibbles by hand to see how R stores data.

A tibble is just a table where:

- Each column is a variable (e.g. species, sepal length)

- Each row is an observation (e.g. one plant)

- Each cell is a single value (i.e. the measurement of that variable for that individual)

Example from last time:

library(tidyverse)

plants <- tibble(

treatment = c("control", "fertilised", "control"),

height_cm = c(15, 20, 13),

survival = c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE)

)

plantsNow, it would be a colossal waste of time if we had to write out each tibble manually!

Typically in R, we read in data from files on our computer or from the internet.

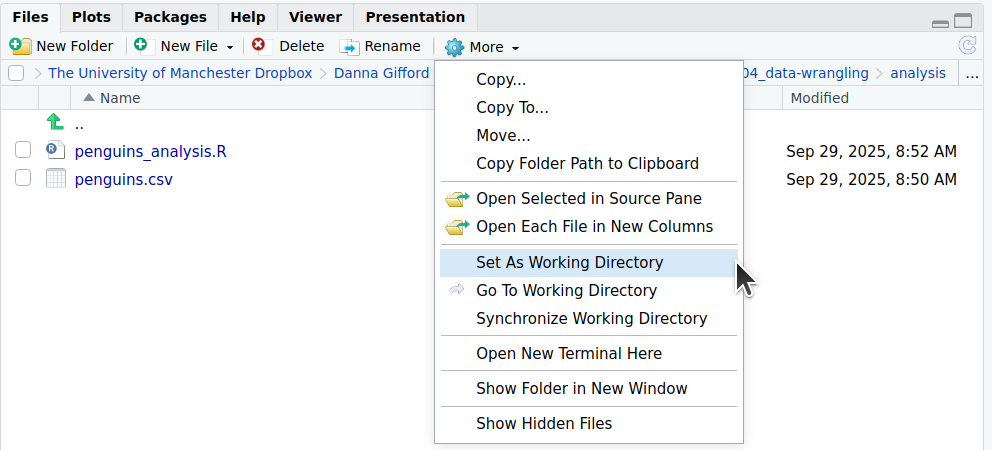

Telling R where to look for data

- Every time R looks for a file, it needs to know where to look.

- The simplest way to do this is to set your working directory, and keep your

.Rscripts and data files together in the same place - Imagine your computer as a giant house 🏡. The working directory is the room you’re currently in. R will look for files within that room. If the file is in another room, R won’t find it unless you give the full address.

You can also set the working directory using the menu:

“Session > Set Working Directory > Choose Directory…”

Or, you can use the Files tab on the right:

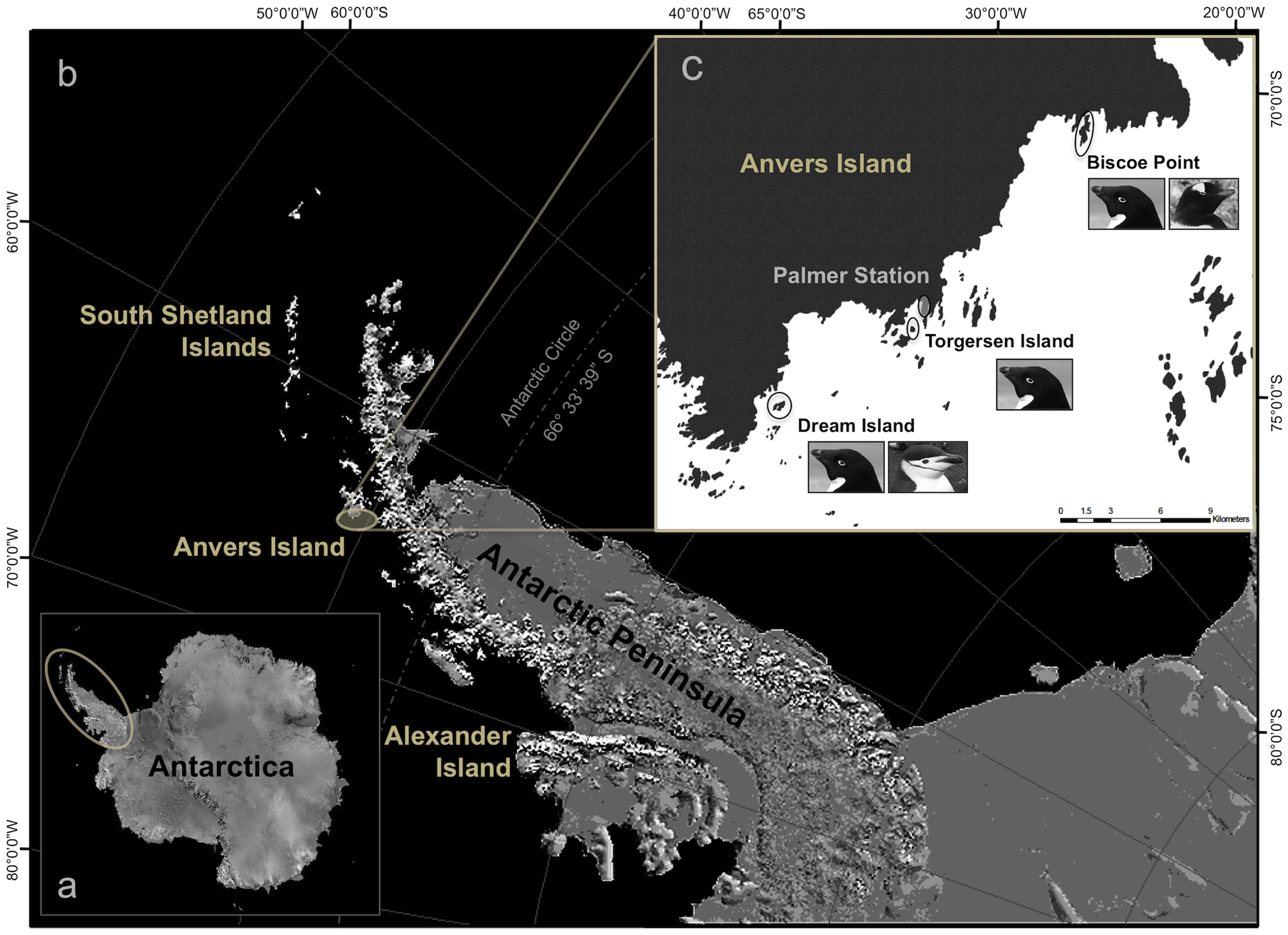

Palmer penguins dataset 🐧

Let’s have a look at some common data wrangling steps using real data.

The palmerpenguins dataset1 contains size measurements for 3 penguin species observed between 2007‒2009 in the Palmer Archipelago, Antarctica, by Dr. Kristen Gorman with the Palmer Station Long Term Ecological Research Program.

If you’re following along in R, please download penguins.csv and save it to your working directory.

Importing data

Most of the time, our data will be stored in CSV files (comma-separated values).

These are simple text files that can be read by almost any program.

In the tidyverse, we use read_csv()1:

library(tidyverse)

# First set working directory to where your file is saved. It looks slightly different on different systems:

setwd("C:/Documents/04_data-wrangling/analysis") # Windows

setwd("/Users/danna/04_data-wrangling/analysis") # Mac

setwd("/home/danna/04_data-wrangling/analysis") # Linux

# Loading the data using read_csv():

# From a file saved on your computer in your working directory

penguins <- read_csv("penguins.csv")

# From a folder called 'data' within your working directory (a 'relative path')

penguins <- read_csv("data/penguins.csv")

# From a file saved somewhere else on your computer (an 'absolute path')

penguins <- read_csv("C:/Documents/data/penguins.csv") # Windows

penguins <- read_csv("/home/username/Documents/data/penguins.csv") # Mac

penguins <- read_csv("/Users/username/Documents/data/penguins.csv") # Linux

# Directly from a URL

penguins <- read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/allisonhorst/palmerpenguins/master/inst/extdata/penguins.csv")Meeting the tibble

When you use read_csv(), R gives you a tibble, just like the ones we wrote by hand.

Typing in the name of the tibble and pressing Ctrl+Enter (Windows/Linux) or Cmd+Enter (Mac) will print the first 10 rows to the Console window:

Looking at the data

Once you have loaded your data, you should check to see if it looks the way you think it should.

There are a few quick ways to peek. You should type these into the Console window.

# A tibble: 6 × 8

species island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm flipper_length_mm body_mass_g

<fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7 181 3750

2 Adelie Torgersen 39.5 17.4 186 3800

3 Adelie Torgersen 40.3 18 195 3250

4 Adelie Torgersen NA NA NA NA

5 Adelie Torgersen 36.7 19.3 193 3450

6 Adelie Torgersen 39.3 20.6 190 3650

# ℹ 2 more variables: sex <fct>, year <int>Rows: 344

Columns: 8

$ species <fct> Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adel…

$ island <fct> Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgerse…

$ bill_length_mm <dbl> 39.1, 39.5, 40.3, NA, 36.7, 39.3, 38.9, 39.2, 34.1, …

$ bill_depth_mm <dbl> 18.7, 17.4, 18.0, NA, 19.3, 20.6, 17.8, 19.6, 18.1, …

$ flipper_length_mm <int> 181, 186, 195, NA, 193, 190, 181, 195, 193, 190, 186…

$ body_mass_g <int> 3750, 3800, 3250, NA, 3450, 3650, 3625, 4675, 3475, …

$ sex <fct> male, female, female, NA, female, male, female, male…

$ year <int> 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007…Data types

In the head() and glimpse() output above, you’ll notice that each column has a designation <abc> either below or beside it. These correspond to the “type” of data each column contains. The main data types you will encounter are listed below:

<chr>meanscharacter, which is text or a mixture of text, numbers & punctuation.

<fct>meansfactor, a special type of text where the levels are pre-defined (e.g. sex).

<dbl>means numbers with decimals,double, a type ofnumeric.

<int>means whole numbers,integer, another type ofnumeric.

<lgl>meanslogical, TRUE/FALSE values (not shown here).

<date>means calendar dates (also not shown here).

This is different from Excel. You should only put data of the same type together in a single column. If you mix data types, it will default to character.

Tidy data

What is tidy data?

A huge amount of effort in analysis goes into cleaning data so that it’s usable. Tidy data gives us a simple, consistent structure that makes analysis, modelling, and visualisation easier.

In tidy data:

- Each variable forms a column

- Each observation forms a row

- Each value is a cell.

Our penguins dataset is already tidy:

# A tibble: 344 × 6

species island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm sex year

<fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <fct> <int>

1 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7 male 2007

2 Adelie Torgersen 39.5 17.4 female 2007

3 Adelie Torgersen 40.3 18 female 2007

4 Adelie Torgersen NA NA <NA> 2007

5 Adelie Torgersen 36.7 19.3 female 2007

6 Adelie Torgersen 39.3 20.6 male 2007

7 Adelie Torgersen 38.9 17.8 female 2007

8 Adelie Torgersen 39.2 19.6 male 2007

9 Adelie Torgersen 34.1 18.1 <NA> 2007

10 Adelie Torgersen 42 20.2 <NA> 2007

# ℹ 334 more rowsThis also ensures different variables measured on the same observation always stay together.

Tidying ‘untidy’ data

Untidy data are arranged in any other way, e.g, when column names are actually values, or when several variables are crammed into one column. Here’s some untidy data on Weddell seals, which also live in Antarctica.

Each column represents a combination of variable and year, so the dataset is not tidy — the years are stored as column headers.

# A tibble: 5 × 5

seal_id length_2022 weight_2022 length_2023 weight_2023

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 W01 260 420 265 430

2 W02 250 390 253 400

3 W03 270 450 275 460

4 W04 255 410 260 420

5 W05 265 430 270 440This layout hides the meaning of the data:

Yearis buried in the column names- Each row mixes multiple observations (2022 and 2023) for the same seal

Making it tidy

We can tidy the seal data by turning those year-specific columns into variables for year, length, and weight.

# A tibble: 10 × 4

seal_id year length weight

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 W01 2022 260 420

2 W01 2023 265 430

3 W02 2022 250 390

4 W02 2023 253 400

5 W03 2022 270 450

6 W03 2023 275 460

7 W04 2022 255 410

8 W04 2023 260 420

9 W05 2022 265 430

10 W05 2023 270 440Now each row is a single observation: one seal, in one year, with one set of measurements

Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii). Image taken by enzofloyd CC-BY-SA 3.0

Cleaning and preparing for analysis

Let’s return to our penguins data.

# A tibble: 344 × 8

species island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm flipper_length_mm body_mass_g

<fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7 181 3750

2 Adelie Torgersen 39.5 17.4 186 3800

3 Adelie Torgersen 40.3 18 195 3250

4 Adelie Torgersen NA NA NA NA

5 Adelie Torgersen 36.7 19.3 193 3450

6 Adelie Torgersen 39.3 20.6 190 3650

7 Adelie Torgersen 38.9 17.8 181 3625

8 Adelie Torgersen 39.2 19.6 195 4675

9 Adelie Torgersen 34.1 18.1 193 3475

10 Adelie Torgersen 42 20.2 190 4250

# ℹ 334 more rows

# ℹ 2 more variables: sex <fct>, year <int>The dataset is already tidy, but that doesn’t mean it’s completely clean. Real datasets often have:

- messy or inconsistent column names,

- extra variables we don’t need,

- values that need to be converted or fixed, or

- missing values.

We often need to clean and prepare imported data before analysis. You can:

rename()columns to make them clearer

select()only the variables you need

filter()rows to focus on certain observations

mutate()to create new variables

arrange()to sort your data

Cleaning and preparing for analysis

Here are some examples of cleaning steps

Rename columns to help understanding:

Select only the columns you need for your analysis:

Subset the data, e.g. to focus on a single species:

Create a new column from existing data:

Dealing with missing values

Sometimes datasets have ‘holes’: a penguin might have been captured but not weighed, for instance. Let’s look at the first ten penguin body mass measurements of our penguins:

The special value NA is how R identifies missing data. What happens if you try to take the mean?

One solution for some functions is to tell R to ignore NA values in its calculations:

However, for some functions, ignoring NA is not possible and R will return an error message.

Sometimes it’s appropriate to remove entries missing values from the dataset entirely

Chaining steps with pipes

Often, we want to do several of these actions in a row.

The pipe operator |> lets us pass the result of one step straight into the next:

penguins |>

remove_missing() |>

filter(species == "Gentoo") |>

mutate(weight_kg = body_mass_g / 1000) |>

select(species, island, weight_kg)Reading this top to bottom is almost like reading a recipe:

- Start with the whole

penguinsdata set

- Filter for the species Gentoo

- Calculate weight in kg

- Select just the columns needed for your analysis

This makes your code readable for both you and anyone else who needs to check it later.

Recap & next steps

- Data wrangling is about preparing data for analysis.

- Always inspect what you imported.

- Tidyverse functions like

filter,mutate,select,arrange,renameare your everyday tools.

- Pipes make your workflow clear and logical.

- Missing values (

NA) are common and should be handled.

You’ve now learned how to import and tidy real biological datasets. Next, we’ll take a look at how to summarise this data using handy functions from the tidyverse.