Exploring correlations

Quantifying relationships between continuous variables

Defining correlation

Correlation tells us how strongly two continuous variables vary together.

Examples in biology:

- Do heavier animals tend to live longer?

- Do larger cells contain more protein?

- Does bacterial growth rate increase with temperature?

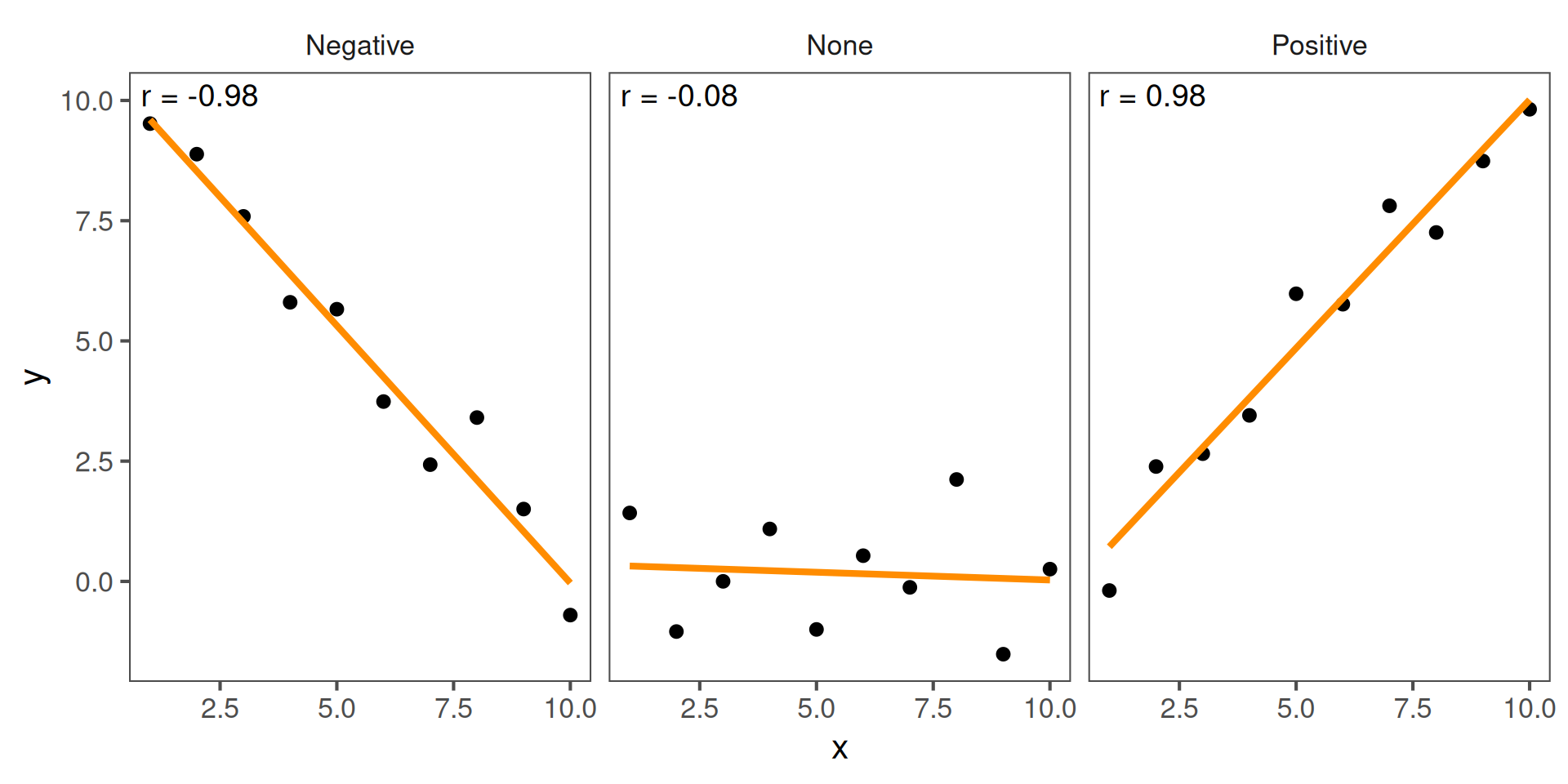

Interpreting patterns

- Positive correlation: as one variable increases, so does the other.

- Negative correlation: as one increases, the other decreases.

- No correlation: no consistent trend.

Quantifying correlation

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) measures linear association:

\[ r = \frac{\text{cov}(x, y)}{s_x s_y} \]

- \(r\) ranges from −1 to +1

- +1: perfect positive linear relationship

- −1: perfect negative

- 0: no linear relationship

Example using real data

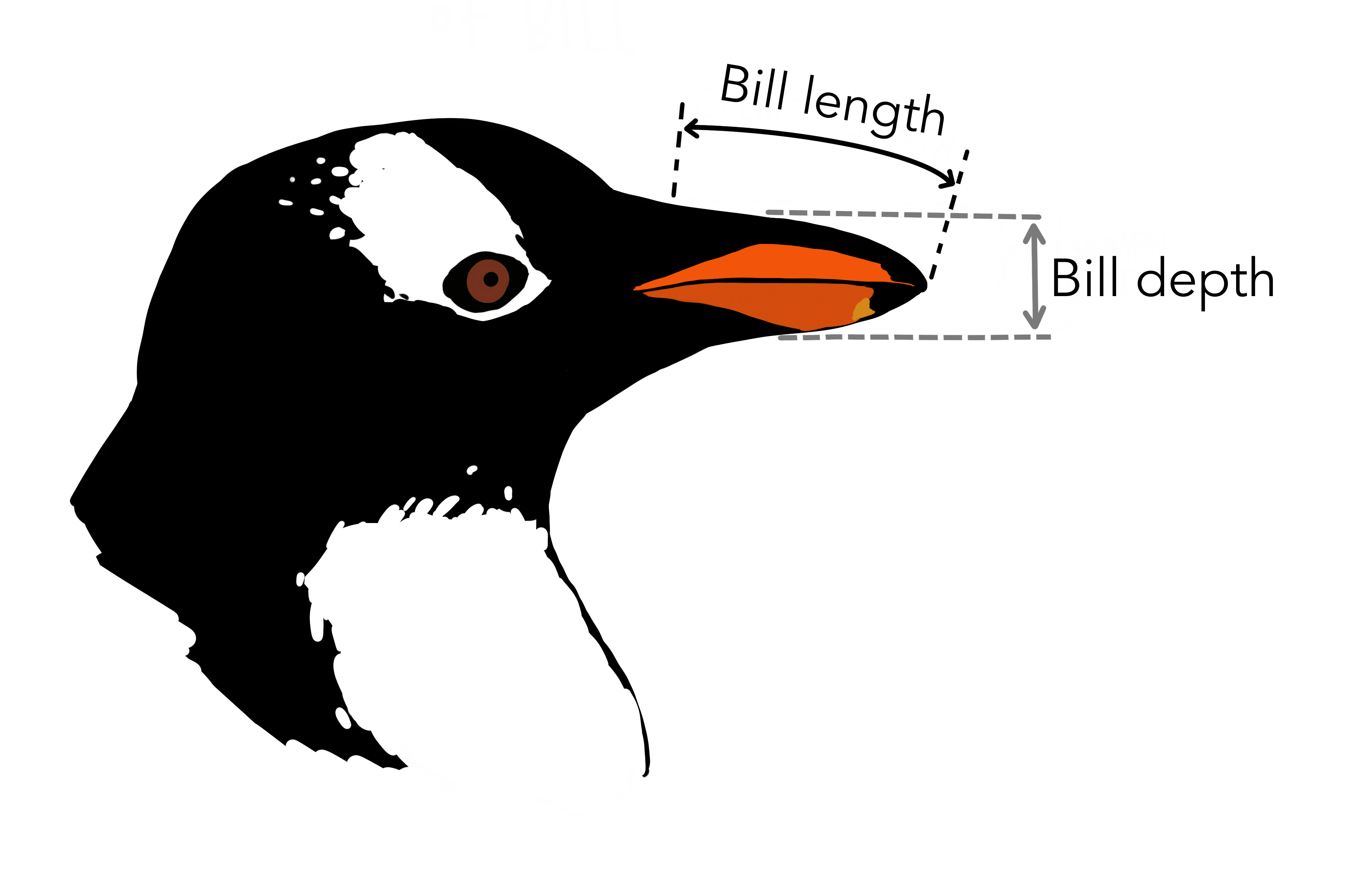

Let’s return to our Palmer Penguins. We’ll look at whether there’s a correlation between bill depth and bill length for Gentoo penguins:

The correlation coefficient r is 0.64, indicating a positive correlation.

Statistical significance for correlations

To test whether the observed r could arise by chance, use a correlation test.

Pearson's product-moment correlation

data: Gentoo$bill_length_mm and Gentoo$bill_depth_mm

t = 9.2447, df = 121, p-value = 1.016e-15

alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

0.5262952 0.7365271

sample estimates:

cor

0.6433839 There is a significant correlation between bill length and depth for Gentoo penguins (Pearson correlation: \(r=0.64\), \(t_{121} = 9.24\), \(p=1\times10^{-15}\)).

Assumptions

Pearson’s correlation assumes:

- Both variables are continuous

- Relationship is linear

- Data are approximately normally distributed

- No major outliers

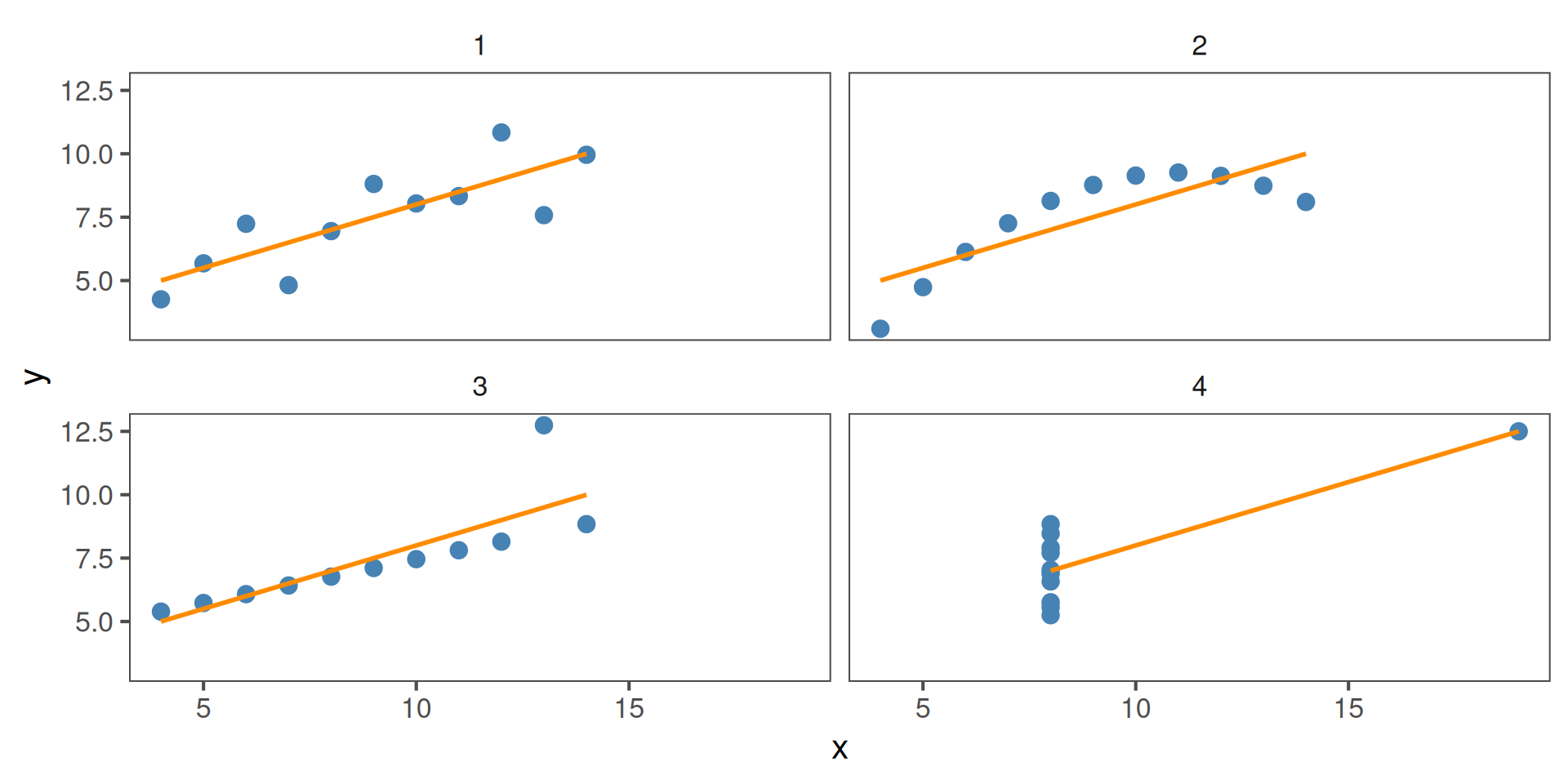

All four of these plots have r = 0.816, but show different data:

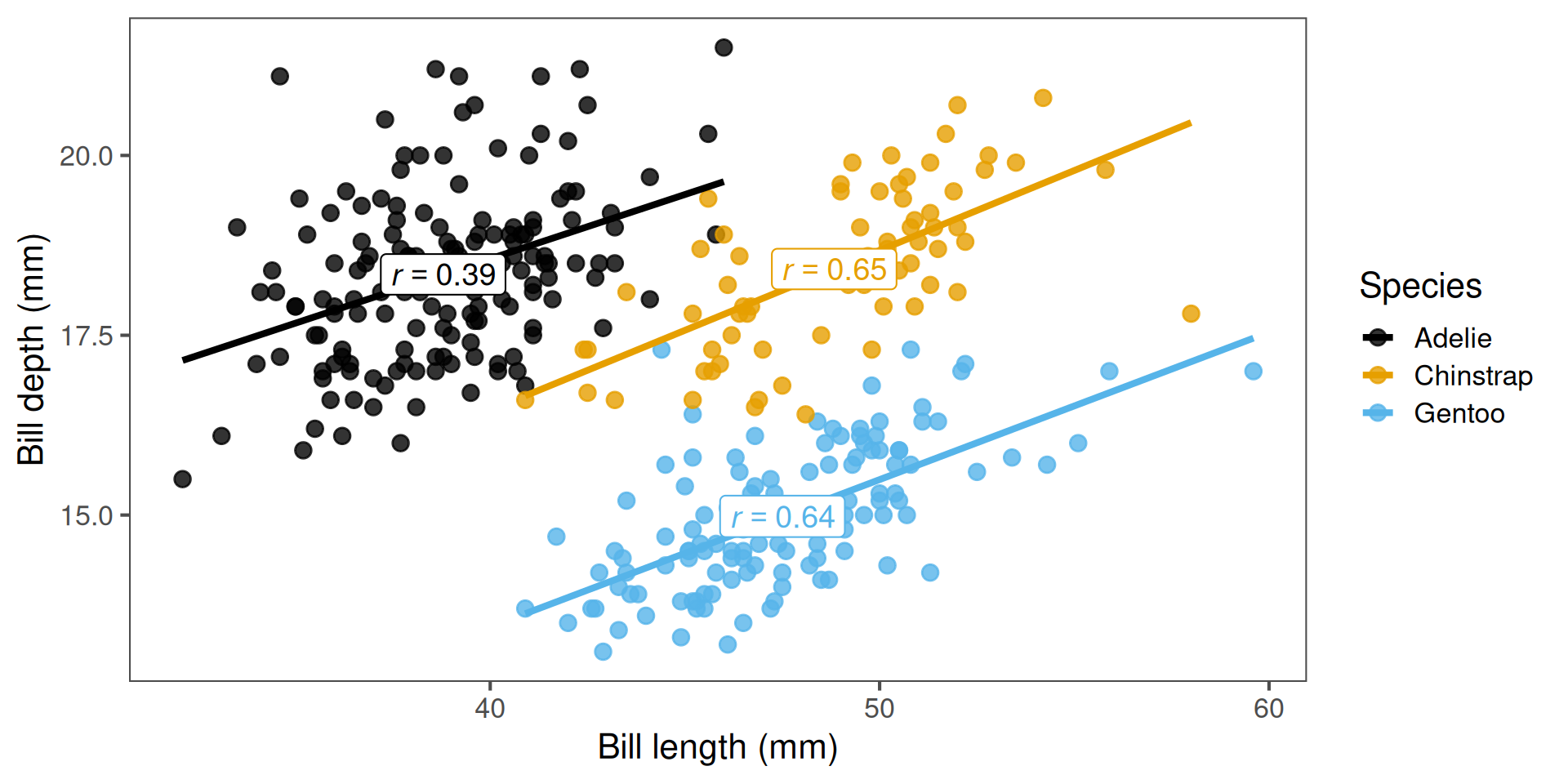

Comparing across groups

Perhaps we want to know if the strength of the correlation differs between species. We can do this using group_by(species) and summarise() from the tidyverse, just like we did previously for means:

penguins |>

group_by(species) |>

summarise(r = cor(x = bill_length_mm,

y = bill_depth_mm,

use = "complete.obs")) # Ignore NAs# A tibble: 3 × 2

species r

<fct> <dbl>

1 Adelie 0.391

2 Chinstrap 0.654

3 Gentoo 0.643Here, Adélie penguins have the lowest correlation between bill length and depth.

Visualising correlations

It’s important to check whether it is reasonable to assume linearity

Rank correlations

When data are not normally distributed, contain outliers, or the relationship is non-linear, we can use a rank-based correlation instead of Pearson’s.

Two common types:

Spearman’s ρ (rho):

- X and Y are converted to ranks (i.e. ordered from smallest to largest)

- A correlation between the ranks of X and Y is performed

- Good for non-linear associations with moderate sample size

Spearman's rank correlation rho

data: Gentoo$bill_length_mm and Gentoo$bill_depth_mm

S = 113069, p-value = 2.919e-15

alternative hypothesis: true rho is not equal to 0

sample estimates:

rho

0.6354081 Rank correlations

When data are not normally distributed, contain outliers, or the relationship is non-linear, we can use a rank-based correlation instead of Pearson’s.

Two common types:

Kendall’s τ (tau):

- Each X and Y observation is paired to every other X and Y observation

- If X and Y change in the same direction for each pair, τ increases

- More robust than Spearman’s for small samples and outliers

- Kendall’s τ will almost always be smaller than Spearman’s ρ

Kendall's rank correlation tau

data: Gentoo$bill_length_mm and Gentoo$bill_depth_mm

z = 7.5905, p-value = 3.188e-14

alternative hypothesis: true tau is not equal to 0

sample estimates:

tau

0.4712505 Summary of key functions in R

| Task | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Calculate correlation | cor(x, y) |

Simple estimate |

| Test correlation | cor.test(x, y) |

Includes p-value |

| Groupwise correlation | group_by() + summarise(cor()) |

Compare groups |

| Non-parametric version | method = "spearman" |

Rank-based test |

Correlation and the coefficient of determination (R2)

The correlation coefficient (r) measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship.

The coefficient of determination (R2) tells us how much of the variation in one variable is explained by the other.

Relationship between them (for simple linear relationships): \[ R^2 = r \times r = r^2 \]

# Compute r and R² for penguins data

r <- cor(x = Gentoo$bill_length_mm,

y = Gentoo$bill_depth_mm,

use = "complete.obs")

# Correlation coefficient r

r[1] 0.6433839[1] 0.4139429For R2, we would report this as: Variation in bill length predicts 41% of the variation in bill depth (R2 = 0.41).

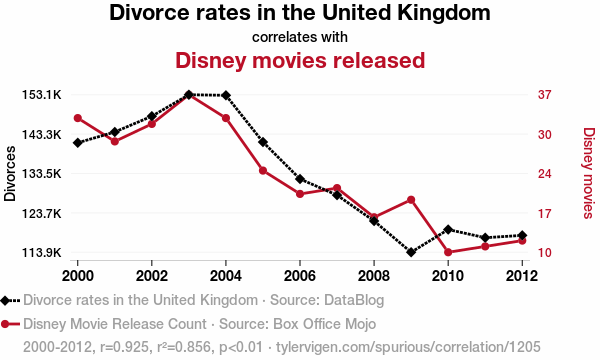

A note on correlation vs. causation

Correlation does not necessarily equal causation. Even if two variables change together, one may not cause the other.

Examples:

- Ice cream sales and shark attacks (both increase with temperature)

- Human height and vocabulary size (both increase with age in children)

- Number of storks and human births (classic spurious correlation)

Correlations can arise due to:

- Confounding variables (a third variable influencing both)

- Coincidence, especially with small or selective datasets

- Indirect relationships, where one variable affects another through an intermediate

We need experiments, controls, or mechanistic understanding to establish causation.

A note on correlation vs. causation

Correlation \(r = 0.925\), \(r^2 = 0.86\). Plot by Tyler Vigen, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Recap & next steps

- Correlation quantifies linear association between two continuous variables

- Visualise first — avoid being misled by non-linear patterns or outliers

- Use Pearson for approximately linear data, Spearman/Kendal otherwise

- Correlation ≠ causation — interpret biologically

You are now ready for the workshop covering hypothesis testing, classical statistical tests, and correlation.